De qual gênero é sua roupa? Representações sociais e atribuição de estereótipos de gênero ao vestuário

RESUMO

O objetivo desse estudo foi compreender as representações sociais acerca da atribuição de gênero ao vestuário. Para isso, contou-se com uma amostra de 256 pessoas que responderam ao Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras (TALP), com os termos indutores “roupa masculina” e “roupa feminina”. Os dados foram analisados por meio da Análise Prototípica, realizada no software Iramuteq. Os resultados indicam para as “roupa masculina” palavras que denotam mais praticidade, conforto e sobriedade, enquanto para as “roupa feminina” as palavras denotam mais variabilidade de peças, bem como foco na estética através de cores e estampas. Conclui-se que as representações sociais, bem como a atribuição de estereótipos em relação ao gênero das roupas, ainda se baseiam numa lógica binária de gênero que indica modos de vestir e de se comportar para os indivíduos.

Palavras-chave: Representações Sociais; Gênero; Estereótipos.

What is the gender of your clothes? Social representations and the attribution of gender stereotypes to clothing

ABSTRACT

This paper’s goal is to comprehend the social representations concerning the attribution of gender to clothing. To that end, a sample of 256 people answered a word association test (Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras – TALP) with stimulus words such as “roupa masculina” and “roupa feminina” (men’s and women’s clothes, respectively). The data have been analyzed through Prototypical Analysis, via Iramuteq software. Results indicate, for “roupa masculina”, words exhibit higher practicality, comfort and sobriety. As for “roupa feminina”, words denote greater clothing variability as well as a focus on aesthetic aspects through colors and prints. In conclusion, social representations, along with stereotypical attribution regarding clothing and gender, are still based on a gender binary rationale that assigns the behavioral code and the dress code to individuals.

Keywords: Social Representations; Gender; Stereotypes.

De qué género es tu ropa? Representaciones sociales y asignación de estereotipos de género a la ropa

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio fue comprender las representaciones sociales sobre la atribución de género a la ropa. Con este fin, se contó con uma muestra de 256 personas que respondieron el Teste de Asociación Libre de Palabras, con los términos inductivos “ropa masculina” y “ropa femenina”. Los datos se analizaron mediante Análisis Prototípico, realizados en software Iramuteq. Los resultados indican para la ropa masculina palabras que denotan más practicidad, comodidad y sobriedad, mientras que para la ropa femenina, las palabras denotan más variabilidad de las piezas, así como enfocarse en la estética a través de colores e impresiones. Se concluye que las representaciones sociales, así como la asignación de estereotipos, en relación con el género de la ropa sigue basándose en una lógica binaria del género que indica formas de vestir y comportarse para los individuos.

Palabras-clave: Representaciones Sociales; Género; Estereotipos.

1. INTRODUÇÃO

A indústria da moda se estabeleceu como uma das mais importantes do mundo. De acordo com a FashionUnited1 (2022), estima-se que ela movimente atualmente três trilhões de dólares globalmente. Esse valor corresponde a 2% do PIB mundial. É também uma indústria que concentra uma significativa força de trabalho, contando com a presença de centenas de milhares de funcionários.

Além de seu impacto econômico, a moda também pode ser entendida enquanto forma de mudança social específica, que se revela em diferentes instâncias da vida social, extrapolando o vestuário e influenciando o comportamento, o consumo, os maneirismos e as influências estéticas vividas pelos indivíduos (Godart, 2010). Estudos de diversas áreas se propuseram a analisar esse fenômeno. Lipovetsky (2009) entende a moda enquanto “dispositivo social”. Calanca (2011) apresenta uma visão sociológica do vestuário. Kawamura (2018) sugere a modalogia como possibilidade de investigação sociológica da moda.

Ao longo da história, a roupa demarcou os diferentes papéis sociais atribuídos aos homens e às mulheres. A diferenciação de gêneros através do vestuário tem como marco inicial a Grande Renúncia do século XIX, quando os homens passaram a se vestir de maneira mais sóbria, enquanto toda a parte ornamental e decorativa do vestuário foi atribuída aos modos de vestir das mulheres. Essa mudança nos códigos do vestuário traz consigo a atribuição de um lugar simbólico e real que atribuía aos homens o espaço público, o trabalho e a independência; e às mulheres, o espaço doméstico, a submissão e a dependência (Crane, 2006; Zambrini, 2010).

A atribuição de gênero às peças de roupa é algo que continua a ser feito na contemporaneidade, demonstrando os impactos das normas de gênero nos modos de ser das pessoas. Ao entrar em grandes lojas do setor de vestuário encontra-se uma evidente divisão entre o setor de peças masculinas, normalmente num espaço menor e com poucas opções de cor, de peças e de modelagens, e o de peças femininas, normalmente num espaço maior e com maior variedade de cores, peças e modelagens. Além de ditar os modos de vestir para homens e mulheres, essas normas tendem a reforçar aspectos presentes na maneira como a sociedade se organiza dentro de um binarismo de gênero (Zambrini, 2010).

Entendendo as repercussões das normas de gênero na maneira de como as pessoas se vestem, alguns questionamentos podem ser disparados: qual é a percepção das pessoas sobre “roupa masculina” e “roupa feminina”? Quais são os estereótipos de gênero são atribuídos às peças de roupa?

Dessa forma, o presente estudo possui como objetivo compreender as representações sociais acerca da atribuição de gênero ao vestuário. Esse trabalho possibilita acessar a forma como os discursos de gênero se insere no cotidiano das pessoas, influindo em sua forma de processar as informações do ambiente, nos modos de ser e se relacionar na contemporaneidade.

2. REFERENCIAL TEÓRICO

2.1 Indústria da Moda: O Gênero das Roupas

Segundo Kawamura (2018), para muitos autores, a moda primeiro começa com a roupa. A palavra “moda” é normalmente utilizada para se referir a roupas ou estilos de aparência, porém ela pode ser usada de diferentes maneiras e possuir diversos significados, estando presente em várias outras esferas da vida social e intelectual.

Conceituar o fenômeno da moda na contemporaneidade é um desafio que, segundo Godart (2010), pode ser entendido de duas formas. A primeira enquanto uma indústria do vestuário e do luxo, local de trabalho de profissionais da área e composta por inúmeras empresas do ramo. Essa perspectiva também considera as formas de consumo de pessoas, grupos e classes sociais que buscam definir sua identidade a partir de seus modos de vestir.

A segunda forma de entendimento considera a moda como uma forma de mudança social específica, que se revela em diferentes instâncias da vida social, não se limita apenas ao vestuário e é um processo regular e não cumulativo. Regular porque sua produção acontece em períodos constantes e, normalmente, curtos; e não cumulativo porque as mudanças ocorridas não acrescentam algo novo às tendências passadas, elas as substituem, transformando-as em algo diferente.

Godart (2010) ressalta que essas duas maneiras de entender o fenômeno da moda estão interligadas, pois a indústria da moda, ao criar estilos de vestuário, está produzindo, ao mesmo tempo, mudanças regulares e não cumulativas que vão influenciar vários âmbitos da vida das pessoas além de seus modos de vestir, como comportamento, consumo, maneirismos e tendências estéticas.

Para Lipovetsky (2009) a história da moda se dá junto à compreensão das mudanças dos estilos e do andamento precipitado das transformações dos modos de vestir. A moda, então, por não possuir um conteúdo próprio que a limite a um objeto específico, se configura como um “dispositivo social” (p. 25) que possui uma duração curta e que influencia diferentes instâncias da vida cotidiana.

Kawamura (2018) apresenta a modalogia como possibilidade de investigação sociológica da moda. Nesta perspectiva a moda é compreendida como um sistema de instituições que produzem tanto o fenômeno quanto a prática da moda. Esse processo também aponta para a produção social de crenças em relação à moda, as quais se manifestam através das roupas.

A atribuição de gênero ao vestuário é um dos valores mais relevantes para o estudo da moda. Para Crane (2006) a roupa é um dos signos mais reconhecíveis de status social e de gênero. Através do vestuário, homens e mulheres percebem e expressam mensagens que integram papéis sociais.

Historicamente a demarcação de gênero por meio do vestuário foi concebida de maneira diferente para mulheres e para homens (Crane, 2006). No século XIX as roupas femininas possuíam caráter ornamental e não adicionavam praticidade para o desempenho de atividades, se configurando enquanto um tipo de controle dirigido ao corpo feminino, que possuía uma delimitação clara entre as esferas pública e privada (Zambrini, 2010; Crane, 2006).

Enquanto isso, os homens no século XIX buscavam uma imagem sóbria e conservadora. Eles também tinham possibilidades de uso de diferentes peças como calças, casacos, gravatas e chapéus, aos quais também eram atribuídos status social e mudavam de acordo com a moda da época (Crane, 2006). De acordo com Braga (2008), ao longo da história, os homens sempre se adornaram, mas, devido às condições da emergência capitalista em meados do século XIX, eles passaram a demonstrar prestígio por aquilo que produziam, não mais pela sua maneira de se vestir.

Desde as décadas de 1960 e 1970, movimentos subversivos vêm sendo experimentados por designers que propunham um deslocamento das fronteiras de gênero. Desde então termos como androginia, moda agênero, moda sem gênero e co-ed surgem na tentativa de democratizar a moda, tornando-a mais diversa e causando tensionamento nas normas binárias vigentes (Githapradana, 2022; Lee et al., 2020).

2.2 Representações Sociais e Atribuição de Estereótipos

De acordo com Sousa e Chaves (2023), as pessoas utilizam os conhecimentos que possuem acerca do mundo para filtrar a quantidade e a qualidade de informações que eles acessam na sociedade através de processos cognitivos e sociais. A partir disso é criado um sistema organizado de opiniões, crenças, valores e informações que mediam as relações entre as pessoas, o seu autoconceito e a interação com os objetos presentes no ambiente. Esse tipo de saber específico é denominado de Representações Sociais (RS) (Moscovici, 2017) e seu estudo se ancora na abordagem psicossociológica da Teoria das Representações Sociais (TRS).

Para a TRS, o conhecimento social integra qualquer tipo de conhecimento criado e partilhado socialmente e não se propõe a avaliar a autenticidade desses saberes, mas a entendê-los como integrantes de uma racionalidade partilhada coletivamente que cria a realidade vivida dos indivíduos. Dessa forma, entende-se que as RS são constructos sociais, produzidas de maneira interativa e, por isso, são concepções dinâmicas da sociedade (Sousa e Chaves, 2023).

As RS possibilitam que as pessoas compreendam e organizem o mundo ao seu redor (Abric, 2001), além de integrarem o processo identitário das pessoas, por possibilitarem a comparação social ocorrida nas relações entre pessoas e entre grupos. Ademais, as RS também orientam na construção de condutas e práticas sociais, bem como possibilitam a legitimação de atitudes e comportamentos em relação ao outro (Sousa e Chaves, 2023).

Uma das possibilidades de análise das RS é a partir da Teoria do Núcleo Central, que faz parte da abordagem estrutural da TRS (Abric, 2001; Sá, 1996; Wachelke e Wolter, 2011; Sousa e Chaves, 2023). Nessa abordagem, as RS são compostas por dois sistemas interdependentes: o sistema (ou núcleo) central e o sistema periférico. Esses sistemas contêm um conjunto de informações, crenças e opiniões acerca de um determinado objeto.

O sistema central possui caráter consensual, é formado por componentes estáveis e consistentes e, por isso, é resistente a mudanças. É ele que organiza e estabiliza os elementos de uma representação através de normas sociais, sendo um gerador de sentido para essa representação. Já o sistema periférico é mais flexível, negociável, dinâmico e se relaciona de maneira mais intensa com os comportamentos, regulando-os e orientando-os, além de legitimar e contextualizar os componentes do sistema central (Abric, 2001; Sá, 1996; Wachelke e Wolter, 2011; Sousa e Chaves, 2023).

Outro fenômeno da cognição social que constitui as relações intergrupais é a atribuição de estereótipos. Esses estereótipos são como as crenças acerca de aspectos específicos de uma categoria social. Eles integram o processo de generalização e, assim como as RS, ajudam os indivíduos a organizarem simbolicamente o ambiente. Os estereótipos são as crenças atribuídas a grupos (Pérez-Nebra e Jesus, 2011; Techio, 2011).

Por meio da Teoria das Relações Intergrupais (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Tajfel, 1982), é possível perceber os estereótipos enquanto componentes do processo de categorização de grupos sociais, possibilitando aos indivíduos que identifiquem e diferenciem pessoas que participam de diferentes grupos sociais, além de legitimar condutas entre os grupos. Assim, os estereótipos possuem a função de atribuir representações positivas ao endogrupo (grupo que o indivíduo faz parte) em relação ao exogrupo (grupo de comparação, o qual o indivíduo não integra) num contexto de conflito entre grupos.

3. METODOLOGIA

3.1 Participantes

A amostra foi composta por 256 participantes, 160 mulheres, 93 homens e 3 pessoas não-binárias (Midade = 32,12, DP = 8,82). A maioria se identifica como heterossexual (N = 164; 64,1%), seguida por bissexual (N = 39; 15,2%), gay (N = 35; 13,7%), lésbica (N = 12; 4,7%) e pansexual (N = 6; 2,3%). A maior parte da amostra é de classe média (N = 121; 47,3%), identifica-se como brancos (N = 141; 55,1%) e possui ensino superior completo (N = 175; 68,4%). Em relação ao posicionamento político dos participantes, a maioria se identifica com de esquerda (N = 120; 46,9%), seguida por centro (N = 91; 35,5%), direita (N = 27; 10,5%), extrema esquerda (N = 16; 6,3%) e extrema direita (N = 2; 0,8%).

3.2 Instrumento

Os participantes responderam ao Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras (TALP), em que se objetivou a identificação do campo semântico em relação à atribuição de gênero à roupa. Foram utilizados enquanto indutores os termos: “roupa masculina” e “roupa feminina”. Foi solicitado aos participantes que registrassem as cinco primeiras palavras que viessem à mente a partir dos estímulos indutores.

3.3 Procedimentos de Coleta e Aspectos Éticos

Os participantes foram convidados a colaborar em um estudo on-line, no mês de março de 2023. O link da pesquisa foi divulgado por meio das redes sociais WhatsApp e Instagram. Antes de os participantes iniciarem, foi apresentado o Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE) que informou sobre a garantia do sigilo e do direito de desistirem da pesquisa a qualquer momento, além de frisar o caráter voluntário da participação. O TCLE foi construído seguindo as recomendações das Resoluções 466/12 e 510/16 do Conselho Nacional de Saúde.

Depois de consentirem com a participação, os participantes relataram suas informações demográficas (idade, gênero, orientação sexual, raça, classe social, educação e posicionamento político). Em seguida os participantes responderam ao Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras (TALP) a partir de dois estímulos: “roupa masculina” e “roupa feminina”. Por fim, os participantes foram agradecidos.

Ressalta-se que o presente estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa com Seres Humanos da Universidade de Fortaleza sob o número de parecer 64127822.0.0000.5052.

3.4 Análise dos Dados

Os dados gerados foram analisados com auxílio do software Iramuteq - Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (Ratinaud, 2009).

As palavras mencionadas no TALP passaram pelo processo de lematização e foram submetidas a Análises Prototípicas, que são técnicas utilizadas para a categorização da representação social de maneira estrutural (Camargo & Justo, 2013; Wachelke & Wolter, 2011). Esse procedimento foi realizado para cada um dos estímulos indutores.

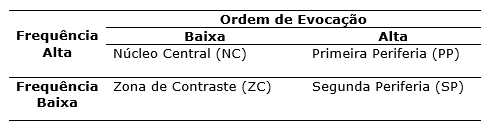

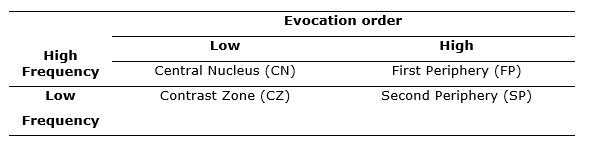

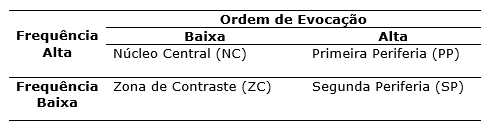

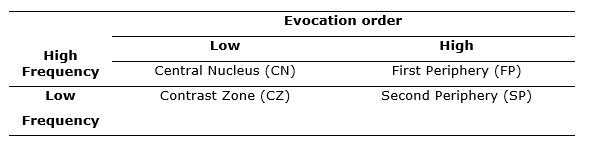

Esse tipo de análise calcula a frequência e a ordem das palavras evocadas pelos participantes e gera um quadro composto por quatro quadrantes (Figura 1): o Núcleo Central (NC) indica as palavras que foram evocadas com maior frequência e mais rapidamente; a Zona Periférica é composta pela Primeira Periferia (PP), que indica as palavras evocadas com uma alta frequência, porém tardiamente, e pela Segunda Periferia (SP), que indica as palavras evocadas com baixa frequência e tardiamente; e a Zona de Contraste (ZC), que indica as palavras que foram evocadas com baixa frequência, porém rapidamente (Camargo & Justo, 2013; Wachelke & Wolter, 2011).

Figura 1. Análise Prototípica

Fonte: Elaborado pelos autores (2024).

4. RESULTADOS E DISCUSSÃO

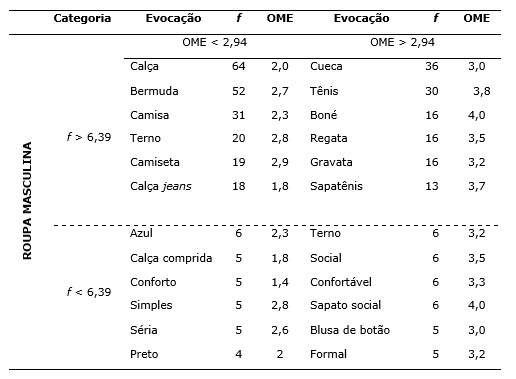

O Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras (TALP) foi utilizado com o intuito de compreender as representações sociais dos participantes acerca da atribuição de gênero ao vestuário. Inicialmente foi solicitado aos participantes que eles listassem as cinco primeiras palavras que lhes viessem à mente quando pensavam na expressão “roupa masculina”. Foram obtidas, ao todo, ٤١٠ evocações. Na Tabela 1, é possível visualizar os principais elementos das representações sociais sobre roupa masculina para os participantes da pesquisa.

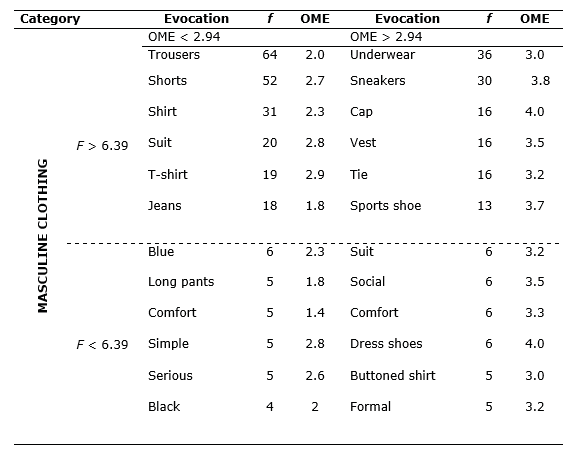

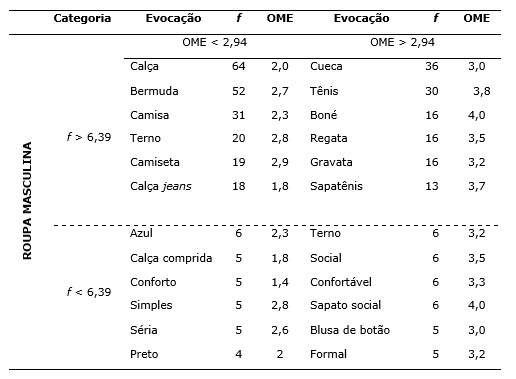

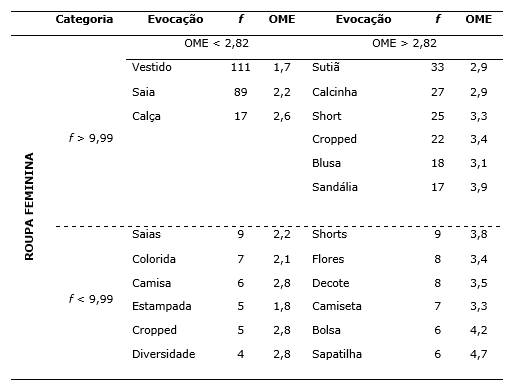

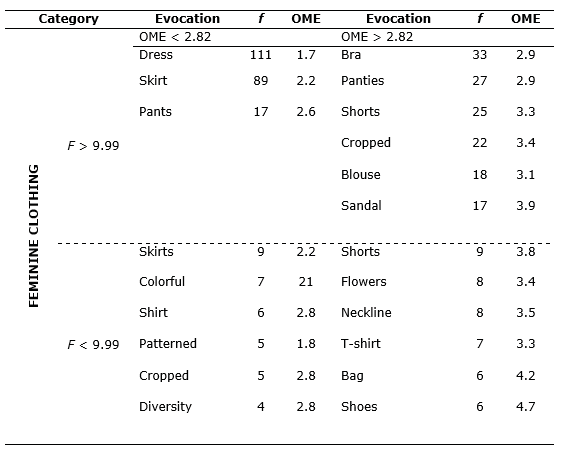

Tabela 1. Análise Prototípica do TALP para o estímulo “roupa masculina”

Fonte: Elaborado pelos autores (2024).

Na Tabela 1, é possível perceber que os principais elementos das representações sociais acerca da ‘‘roupa masculina” para os participantes estão fortemente associados às palavras “calça”, “bermuda”, “camisa”, “terno” e “camiseta”. Essas palavras, localizadas no primeiro quadrante da Tabela 1, constituem o Núcleo Central (NC) da representação social do fenômeno em questão para a amostra, ou seja, apresenta de forma estrutural a noção mais fortemente compartilhada pelo grupo e as palavras de mais alta frequência.

Nas Zonas Periféricas, localizadas nos segundo e quarto quadrantes da Tabela 1, surgiram palavras que ilustram a representação de roupa masculina para os participantes. Na primeira periferia, ilustrada no segundo quadrante, localizam-se palavras de alta frequência e alta evocação, de modo que complementa o sentido do NC e o protege. Para os respondentes, as palavras listadas com maior frequência foram “cueca”, “tênis”, “boné” e “regata”.

Na segunda periferia, correspondente ao quarto quadrante da Tabela 1, localizam-se as palavras de menor frequência e maior ordem de evocação, relacionando-se mais fortemente com as experiências individuais de cada participante. As palavras com maior frequência foram: “terno”, “social” e “confortável”.

A Zona de Contraste, localizada no terceiro quadrante da Tabela 1, corresponde aos elementos que foram prontamente evocados e com uma frequência abaixo da média, indicando uma possível direção de mudança na representação social. Aqui, as palavras citadas com maior frequência foram: “azul”, “calça comprida” e “conforto”. Nota-se que não há um contraste significativo entre as palavras das demais zonas, o que pode indicar que a representação social sobre roupa masculina se encontra estável.

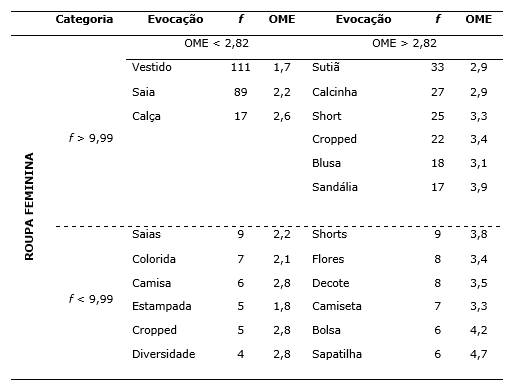

Depois os participantes foram convidados a listarem as cinco primeiras palavras que lhes viessem à mente quando pensavam na expressão “roupa feminina”. Foram obtidas, ao todo, ٣٤٦ evocações. Na Tabela 2, é possível visualizar os principais elementos das representações sociais sobre roupa feminina para os participantes da pesquisa.

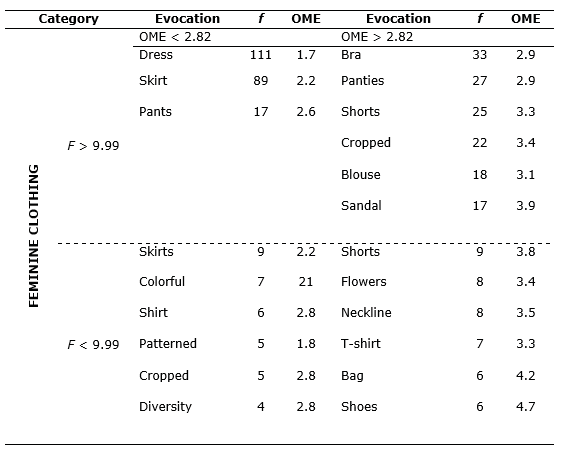

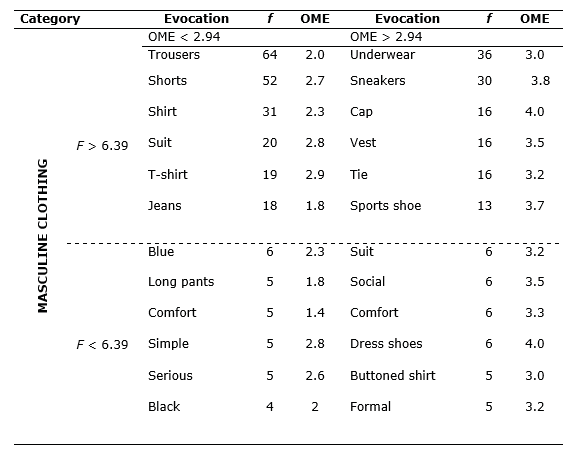

Tabela 2. Análise Prototípica do TALP para o estímulo “roupa feminina”

Fonte: Elaborado pelos autores (2024).

Na Tabela 2 são apresentados os elementos principais da representação social de “roupa feminina” para os participantes. Verificou-se que estes elementos estão fortemente associados às palavras “vestido”, “saia” e “calça”, formando, assim, o Núcleo Central da representação.

Nas Zonas Periféricas, localizadas nos segundo e quarto quadrantes da Tabela 2, surgiram palavras que ilustram a representação da roupa feminina para os respondentes. Na primeira periferia, no segundo quadrante, localizam-se as palavras “sutiã”, “calcinha”, “short” e “cropped”, como sendo as com maior evocação. Em relação à segunda periferia, correspondente ao quarto quadrante da Tabela 2, as palavras com maior frequência foram: “shorts”, “flores” e “decote”.

Na Zona de Contraste, localizada no terceiro quadrante da Tabela 2, as palavras com maior frequência foram: “saias”, “coloridas” e “camisa”. Nota-se que não há um contraste significativo entre as palavras das demais zonas, o que pode indicar que a representação social sobre roupa feminina se encontra estável.

Nota-se que há diferenças nas evocações referentes aos tipos de roupa relacionada a cada gênero, sendo as roupas masculinas representadas por peças que proporcionam mais conforto e mobilidade, além de serem mais sóbrias do que as femininas. Em suma, é perceptível a atribuição de estereótipos de gênero às peças de roupa pelos participantes da pesquisa. Esse resultado reforça a ideia de Crane (٢٠٠٦) da roupa enquanto um dos símbolos mais perceptíveis de gênero e status social. Para a autora, as roupas integram o processo da criação de identidades sociais e se constituem como uma forma de afirmação e produção de comportamento.

As diferenças na forma de encarar roupas “masculina” e “feminina” pelos participantes da pesquisa parecem compor um processo de análise herdado do século XIX, quando a roupa passou a integrar o processo de diferenciação entre os gêneros masculino e feminino (Kawamura, 2018; Crane, 2006) e a ocupar um lugar privilegiado, dentro de uma lógica binária, no processo de demarcação e delimitação das fronteiras de gênero (Zambrini, 2010;2016).

Os resultados da pesquisa vão ao encontro do apresentado por Hyde (2005, 2019) de que, em termos de traços, habilidades, interesses e comportamentos, homens e mulheres não se enquadram em duas categorias completamente distintas. Isso porque individualmente homens e mulheres podem expressar uma mistura de atributos e comportamentos tidos como “masculinos” e femininos”. Já Lennon (2017) apresentou resultados de que o uso de itens específicos, culturalmente, informa o sexo biológico. Como exemplo, o autor denota a designação de gênero dos corpos de bebês lidos como masculinos ou femininos através do uso das cores azul e rosa.

Morgenroth e Ryan (2020) apontam para a hipótese de que o binarismo de gênero/sexo é criado e reforçado através da performatividade de gênero/sexo atrelado ao sujeito (homem/mulher), traje (corpo e aparência) e roteiro (comportamentos, trejeitos e preferências). Essa expectativa pode ser percebida através das respostas da pesquisa, nas quais esteve presente o reconhecimento de que a roupa pode reforçar os estereótipos de gênero, bem como o quanto esses criam a expectativa sobre o que cada gênero pode ou não vestir. A roupa pode ser compreendida aqui como item de expressão da identidade ao mesmo tempo que assume um caráter de instrumento de adequação social.

Akdemir (2018a) concorda que o modo de se vestir varia de acordo com o grupo social ocupado pelo sujeito e que as roupas carregam signos visíveis de expressão e identificação através de cores, modelagens, tecidos e elementos visuais. A comunicação por meio do vestuário evidencia normas que são partilhadas pelos membros de um grupo e pode se transformar em signos identificáveis para aqueles que não fazem parte desse grupo. Esse fenômeno pode ser compreendido, como sugere Tajfel (1982), como parte do processo de categorização social em que o exogrupo tende a ser analisado enquanto um grupo homogêneo, ou seja, composto por integrantes parecidos entre si. Porém, essa análise é baseada na generalização, que possibilita uma visão estereotipada dos grupos em questão.

Dutra (2002) afirma que a moda, historicamente, não é vista como atributo masculino, sendo atribuída a futilidade e capricho relacionados às mulheres. As respostas da pesquisa trazem à tona essa realidade na atribuição de mais elementos de moda na “roupa feminina” como cores, estampas e variedade de peças. Em paralelo a isso, às roupas masculinas são atribuídas mais sobriedade e pouca variedade de cor e peças.

Ao escrever sobre a crítica que algumas feministas fazem a essa lógica binária de que a moda ocupa mais mulheres do que homens, Kawamura (2018) afirma que a moda pode ser entendida como um mecanismo de controle dos corpos femininos que reduz os horizontes sociais, culturais e intelectuais das mulheres. Elas passam a usar seu tempo e dinheiro com a beleza, e isso se torna uma opressão, gerando uma “falsa consciência” daquilo que elas passam a acreditar que é uma prioridade: as roupas e a aparência.

Akdemir (2018b) assinala que a moda possui um importante papel na desconstrução de estereótipos de gênero e que, atualmente, percebe-se o quanto as maneiras de vestir têm se atualizado: apresentando roupas masculinas “feminilizadas” e roupas femininas “masculinizadas”, concordando com tendências como a moda agênero (Lee et al., 2020) e co-ed (Githapradana, 2022). Os resultados encontrados na pesquisa mostram que esse discurso de uma moda mais diversa e subversiva às normas de gênero parece estar distante da realidade dos participantes que ainda possuem uma lente binária em seu processo de análise e atribuição de estereótipos.

5. CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS

O vestuário faz parte do cotidiano das pessoas e, além de possuir uma função objetiva de proteção do corpo, assume funções sociais que extrapolam o simples ato de se cobrir. Desde dispositivo social até símbolo, dos mais notáveis, de status social e de gênero, as roupas comunicam algo sobre aqueles que as vestem.

A moda, ao longo do tempo, tendeu a reforçar os estereótipos de gênero por meio da divisão do que se compreende como roupa masculina e roupa feminina. Esse processo tem como base uma lógica binária de gênero que permeia todas as instâncias da vida social das pessoas, as quais passam a encarar o mundo por essa lente.

Os participantes da pesquisa tenderam a corroborar com essa lógica binária em sua leitura do processo de generificação do vestuário. A partir do uso do TALP, foi possível se aproximar das representações sociais dos participantes acerca do que seria “roupa masculina” e “roupa feminina” para eles. Às “roupas masculinas” foram atribuídas palavras que indicam praticidade, sobriedade e conforto, enquanto para as “roupas femininas” foram atribuídas palavras que indicam uma variedade maior de peças e com foco na estética presente no sortimento de cores e estampas.

Notou-se que as palavras presentes no Núcleo Central parecem estar protegidas para ambos os indutores, significando uma estabilidade nas representações sociais apontadas pelos participantes. Esse dado reforça a ideia do quanto a lógica binária ainda opera na forma como as pessoas entendem e consomem produtos de moda. Mesmo reconhecendo uma tendência subversiva do gênero em alguns movimentos dentro da moda – moda agênero, moda sem gênero e co-ed – essa realidade ainda parece estar distante da realidade da maioria das pessoas.

Esse estudo possibilitou um olhar para o desenvolvimento de estudos futuros na área de moda, estudos de gênero e RS que possam considerar realidades específicas de consumo, interseccionalidade com alguns marcadores sociais, como sexualidade, raça e geração, e os impactos das RS na criação e produção de produtos de moda. Algumas limitações foram percebidas ao longo dessa pesquisa, como a forma de acessar os interlocutores via redes sociais, que limita o acesso de pessoas que não estejam presentes nesse contexto.

Não obstante essa pesquisa traz importantes contribuições tanto científicas, na produção de conhecimento nas áreas da Moda e da Psicologia Social, quanto sociais, na demonstração para a sociedade do quanto a roupa é um dos elementos centrais dentro das relações humanas.

Notas de fim de texto

¹ FashionUnited é uma plataforma independente de levantamento e compartilhamento de dados referentes à indústria da moda internacional.

REFERÊNCIAS

ABRIC, J C. Prácticas sociales y representaciones. México: Coyoacán, 2001.

AKDEMİR, Nihan. Visible Expression of Social Identity: the clothing and fashion. Gaziantep University Journal Of Social Sciences, [S.L.], v. 17, n. 4, p. 1371-1379, 2018a. http://dx.doi.org/10.21547/jss.411181. Disponível em: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jss/issue/39349/411181. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

AKDEMIR, Nihan. Deconstruction of Gender Stereotypes Through Fashion. European Journal Of Social Science Education And Research, S.L, v. 5, n. 2, p. 185-190, 2018b. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326662785_Deconstruction_of_Gender_Stereotypes_Through_Fashion. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

BRAGA, João. História da moda: uma narrativa. 6. ed. São Paulo: Editora Anhembi Morumbi, 2008.

CAMARGO, Brígido V.; JUSTO, Ana M.. IRAMUTEQ: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, [S.L.], v. 21, n. 2, p. 513-518, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/tp2013.2-16. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S1413-389X2013000200016&script=sci_abstract&tlng=en. Acesso em: 25 mar. 2024.

CALANCA, Daniela. História social da moda. São Paulo: Senac, 2011.

CRANE, Diana. A moda e seu papel social: classe, gênero e identidade das roupas. 2. ed. São Paulo: Senac, 2006.

DUTRA, J. L. “Onde você comprou esta roupa tem para homem?”: a construção de masculinidades nos mercados alternativos de moda. In: GOLDENBERG, Mirian (org.). Nú e vestido: dez antropólogos revelam a cultura do corpo carioca. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2002. p. 359-411.

GITHAPRADANA, Dewa Made Weda. Aesthetics and Symbolic Meaning of Androgynous and CO-ED Style Trends in Men’s Fashion. Humaniora, [S.L.], v. 13, n. 1, p. 23-32, 15 fev. 2022. Universitas Bina Nusantara. http://dx.doi.org/10.21512/humaniora.v13i1.7378. Disponível em: https://journal.binus.ac.id/index.php/Humaniora/article/view/7378. Acesso em: 15 de abril de 2023.

GODART, Frédéric. Sociologia da Moda. São Paulo: Senac, 2010.

HYDE, Janet Shibley. The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, [S.L.], v. 60, n. 6, p. 581-592, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.6.581. Disponível em: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-606581.pdf. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

HYDE, Janet Shibley; BIGLER, Rebecca S.; JOEL, Daphna; TATE, Charlotte Chucky; VAN ANDERS, Sari M.. The future of sex and gender in psychology: five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, [S.L.], v. 74, n. 2, p. 171-193, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000307. Disponível em: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-32185-001. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

KAWAMURA, Y. Fashion-ology: an introduction to fashion studies. 2. ed. Londres: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

LEE, Hoe Ryung; KIM, Jongsun; HA, Jisoo. ‘Neo-Crosssexual’ fashion in contemporary men’s suits. Fashion And Textiles, [S.L.], v. 7, n. 1, p. 1-28, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40691-019-0192-2. Disponível em: https://fashionandtextiles.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40691-019-0192-2. Acesso em 16 de abril de 2023.

LENNON, Sharron J.; ADOMAITIS, Alyssa Dana; KOO, Jayoung; JOHNSON, Kim K. P. Dress and sex: a review of empirical research involving human participants and published in refereed journals. Fashion And Textiles, [S.L.], v. 4, n. 1, p. 1-21, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40691-017-0101-5. Disponível em: https://fashionandtextiles.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40691-017-0101-5. Acesso em: 23 mar. 2024.

LIPOVETSKY, Gilles. O império do efêmero: a moda e seu destino nas sociedades modernas. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2009.

MOSCOVICI, Serge. Representações sociais: investigações em psicologia social. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2017.

PÉREZ-NEBRA, Amalia Raquel; JESUS, Jaqueline Gomes de. Preconceito, Estereótipo e Discriminação. In: TORRES, Cláudio Vaz; NEIVA, Elaine Rabelo (org.). Psicologia social: principais temas e vertentes. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. Cap. 10. p. 219-237.

SÁ, Celso Pereira de. Núcleo central das representações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 1996.

MORGENROTH, Thekla; RYAN, Michelle K.. The Effects of Gender Trouble: an integrative theoretical framework of the perpetuation and disruption of the gender/sex binary. Perspectives On Psychological Science, [S.L.], v. 16, n. 6, p. 1113-1142, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745691620902442. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32375012/. Acesso em: 23 mar. 2024.

RATINAUD, P. Iramuteq: interface de r pour les analyses multidimensionnelles de textes et de questionnaires, 2009. Disponível em: www.iramuteq.org. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2024.

SOUSA, Yuri Sá Oliveira; CHAVES, Antonio Marcos. Representações Sociais. In: TORRES, Ana Raquel Rosas et al (org.). Psicologia Social: temas e teorias. 3. ed. São Paulo: Blucher, 2023. Cap. 8. p. 277-306.

TAJFEL, H. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Annual Review Of Psychology, [S.L.], v. 33, n. 1, p. 1-39, 1982. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245. Disponível em: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1982-12052-001. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2024.

TAJFEL, H; TURNER, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In: AUSTIN, W G; WORCHEL, S (ed.). The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, 1979. p. 33-47.

TECHIO, E. M. . Estereótipos Sociais como Preditores das Relações intergrupais. In: TECHIO, Elza Maria; LIMA, Marcus Eugênio Oliveira. (Org.). Cultura e Produção das Diferenças: estereótipos e Preconceito no Brasil, Espanha e Portugal. Brasília: Technopolitik, 2011, p. 21-75.

WACHELKE, João; WOLTER, Rafael. Critérios de construção e relato da análise prototípica para representações sociais. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, [S.L.], v. 27, n. 4, p. 521-526, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0102-37722011000400017. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/ptp/a/bdqVHwLbSD8gyWcZwrJHqGr/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

ZAMBRINI, Laura. Modos de vestir e identidades de género: reflexiones sobre las marcas culturales sobre el cuerpo. Revista de Estudios de Género Nomadías, S. L., n. 11, 2010. Disponível em: https://nomadias.uchile.cl/index.php/NO/article/view/15158. Acesso em: 20 de março de 2023.

ZAMBRINI, Laura. Olhares sobre moda e design a partir de uma perspectiva de gênero. dObra[s] – revista da Associação Brasileira de Estudos de Pesquisas em Moda, [S. l.], v. 9, n. 19, p. 53–61, 2016. DOI: 10.26563/dobras.v9i19.452. Disponível em: https://dobras.emnuvens.com.br/dobras/article/view/452. Acesso em: 20 de março de 2023.

What is the gender of your clothes? Social representations and the attribution of gender stereotypes to clothing

ABSTRACT

This paper’s goal is to comprehend the social representations concerning the attribution of gender to clothing. To that end, a sample of 256 people answered a word association test (Free Word Association Test – FWAT) with stimulus words such as “roupa masculina” and “roupa feminina” (men’s and women’s clothes, respectively). The data have been analyzed through Prototypical Analysis, via Iramuteq software. Results indicate for “roupa masculina” words exhibiting higher practicality, comfort and sobriety. As for “roupa feminina”, words denote greater clothing variability as well as a focus on aesthetic aspects through colors and prints. In conclusion, social representations, along with stereotypical attribution regarding clothing and gender, are still based on a gender binary rationale that assigns the behavioral code and the dress code to individuals.

Keywords: Social Representations; Gender; Stereotypes.

De qual gênero é sua roupa? Representações sociais e atribuição de estereótipos de gênero ao vestuário

RESUMO

O objetivo desse estudo foi compreender as representações sociais acerca da atribuição de gênero ao vestuário. Para isso, contou-se com uma amostra de 256 pessoas que responderam ao Teste de Associação Livre de Palavras (TALP), com os termos indutores “roupa masculina” e “roupa feminina”. Os dados foram analisados por meio da Análise Prototípica, realizada no software Iramuteq. Os resultados indicam para “roupa masculina” palavras que denotam mais praticidade, conforto e sobriedade, enquanto para “roupa feminina” palavras que denotam mais variabilidade de peças, bem como foco na estética por meio de cores e estampas. Conclui-se que as representações sociais, bem como a atribuição de estereótipos em relação ao gênero das roupas, ainda se baseiam numa lógica binária de gênero, indicadora de modos de vestir e de se comportar para os indivíduos.

Palavras-chave: Representações Sociais; Gênero; Estereótipos.

De qué género es tu ropa? Representaciones sociales y asignación de estereotipos de género a la ropa

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio fue comprender las representaciones sociales sobre la atribución de género a la ropa. Con este fin, se contó con uma muestra de 256 personas que respondieron el Teste de Asociación Libre de Palabras, con los términos inductivos “ropa masculina” y “ropa femenina”. Los datos se analizaron mediante Análisis Prototípico, realizados en software Iramuteq. Los resultados indican para la “ropa masculina” palabras que denotan más practicidad, comodidad y sobriedad, mientras que para la “ropa feminina” palabras que denotan más variabilidad de las piezas, así como enfocarse en la estética a través de colores e impresiones. Se concluye que las representaciones sociales, así como la asignación de estereotipos, en relación con el género de la ropa sigue basándose en una lógica binaria del género que indica formas de vestir y comportarse para los individuos.

Palabras-clave: Representaciones Sociales; Género; Estereotipos.

1. INTRODUCTION

The fashion industry has established itself as one of the most important industries in the world in economic terms, amassing a significant workforce. According to data from FashionUnited (2016), an independent platform for collecting and sharing data on the international fashion industry, it is estimated that the industry currently generates three trillion dollars globally – a value that corresponds to 2% of the world’s GDP.

In addition to its economic impact, fashion can also be understood as a form of specific social change, which can be seen in different instances of social life, moving beyond just clothing and being able to influence behavior, consumption, mannerisms and aesthetic influences experienced by individuals (Godart, 2010). Studies from various areas have proposed to analyze this phenomenon: Lipovetsky (2009) understands fashion as a “social device”; Calanca (2011) presents a sociological view of clothing; and Kawamura (2018) suggests fashionology as a possibility for sociological investigation of fashion.

Throughout history, clothing has marked the different social roles attributed to men and women. The differentiation of genders through clothing began with the Great Male Renunciation of the 19th century, when men began to dress more seriously, while all the ornamental and decorative aspects of clothing were attributed to female ways of dressing. This change in clothing codes brought with it the attribution of a symbolic and real place, which attributed to men the public space, work and independence; and, to women, the domestic space, submission and dependence (Crane, 2006; Zambrini, 2010).

The attribution of gender to clothing items is something that continues in contemporary times, demonstrating the impacts of gender norms on people’s ways of being. When entering large clothing stores, one finds a clear division between the men’s clothing section, usually in a smaller space with few options in terms of colors, pieces and styles, and the women’s clothing section, usually in a larger space with a greater variety of colors, pieces and styles. In addition to dictating the ways in which men and women should dress, these norms tend to reinforce aspects present in the way society is organized within a gender binary (Zambrini, 2010).

Understanding the repercussions of gender norms on the way people dress, some questions can be raised: what is the individual’s perception of “masculine clothing” and “feminine clothing”? What are the gender stereotypes attributed to clothing items?

Thus, the present study aims to understand the social representations in regard to the attribution of gender to clothing. This work makes it possible to access the ways in which gender discourses are inserted into people’s daily lives, influencing ways of processing information from the environment, of being and of relating in contemporary times.

The theoretical framework addresses, through bibliographic research, the relationship between the fashion industry and the gender of clothing, as well as social representations and the attribution of stereotypes. Additionally, based on applied research, the Free Word Association Test (FWAT) was used as a data collection instrument, with the inducing terms “masculine clothing” and “feminine clothing”, applied to a sample of 256 people, whose data were analyzed using Prototypical Analysis, carried out in the Iramuteq software.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 The Fashion Industry and the Gender of Clothing

According to Kawamura (2018), for many authors, fashion first begins with clothing. The word “fashion” is normally used to refer to clothing or styles of appearance, but it can be used in different ways and have different meanings, being present in several other spheres of social and intellectual life.

Conceptualizing the phenomenon of fashion in contemporary times is a challenge that, according to Godart (2010), can be understood in two ways. The first as a clothing and luxury industry, a workplace for professionals in the area and composed of numerous companies in the sector. This perspective also considers the forms of consumption of people, groups and social classes that seek to define their identity based on their ways of dressing. The second considers fashion as a specific form of social change, which is revealed in different instances of social life, it is not limited to clothing and is a regular and non-cumulative process – regular because its production occurs in constant and usually short periods; and non-cumulative because the changes that occur do not add anything new to past trends, they replace them, transforming them into something different.

Godart (2010) also emphasizes that these two ways of understanding the phenomenon of fashion are interconnected, since the fashion industry, when creating clothing styles, is producing, at the same time, regular and non-cumulative changes that will influence various areas of people’s lives beyond their ways of dressing, these include behavior, consumption, mannerisms and aesthetic trends.

For Lipovetsky (2009), the history of fashion occurs together with the understanding of changes in styles and the rapid pace of transformations in ways of dressing. Therefore, because fashion does not have its own content that limits it to a specific object, it is configured as a “social device” (Lipovetsky, 2009, p. 25), which has a short duration and influences different areas of everyday life.

Kawamura (2018) presents fashionology as a possibility for sociological investigation of fashion. From this perspective, fashion is understood as a system of institutions that produce both the phenomenon and the practice of fashion. This process also points to the social production of beliefs in relation to fashion, which are manifested through clothing.

This research highlights that the attribution of gender to clothing is one of the most relevant values for the study of fashion. For Crane (2006), clothing is one of the most recognizable signs of social status and gender. Through clothing, men and women perceive and express messages that integrate social roles.

Historically, the demarcation of gender through clothing has been conceived differently for women and men (Crane, 2006). In the 19th century, women’s clothing was ornamental and did not add practicality to the range of activities, configuring itself as a type of control directed at the female body, which had a clear delimitation between the public and private spheres (Zambrini, 2010; Crane, 2006).

Meanwhile, men sought a serious and conservative image in the 19th century. They also had the possibility of wearing different pieces, such as pants, coats, ties and hats, to which social status was also attributed and which changed according to the fashion of the time (Crane, 2006). According to Braga (2008), throughout history, men have always adorned themselves, but due to the conditions of capitalism’s emergence in the mid-19th century, they began to demonstrate prestige not through the way they dressed but by what they produced.

Since the 1960s and 1970s, subversive movements have been experimented with by designers who proposed a shift in gender boundaries. Since then, terms such as androgynous, agender, genderless and co-ed fashion have emerged in an attempt to democratize fashion, making it more diverse and causing tension in the current binary norms (Githapradana, 2022; Lee et al., 2020).

2.2 Social Representations and Stereotype Attribution

According to Sousa and Chaves (2023), people use the knowledge they have about the world to filter the quantity and quality of information accessed in society through cognitive and social processes. From this, an organized system of opinions, beliefs, values, and information is created. This system mediates the relationships between people, their self-concept, and their interaction with objects present in the environment. This type of specific knowledge is called Social Representations (SR) (Moscovici, 2017) and its study is anchored in the psychosociological approach of the Theory of Social Representations (TSR).

For TSR, social knowledge consists of any type of knowledge created and shared socially, not to evaluate the authenticity of this knowledge, but to understand it as part of a collectively shared rationality, which in turn creates the lived reality of individuals. Thus, it is understood that SRs are social constructs, produced in an interactive manner and, therefore, are dynamic conceptions of society (Sousa; Chaves, 2023).

SRs enable people to understand and organize the world around them (Abric, 2001), in addition to integrating people’s identity processes, by enabling social comparison that occurs in relationships between people and groups. Furthermore, SRs also guide the construction of social conduct and practices, as well as enabling the legitimization of attitudes and behaviors in relation to others (Sousa; Chaves, 2023).

One of the possibilities for analyzing SRs arises from the Central Nucleus Theory, which is part of the structural approach of the TSR (Abric, 2001; Sá, 1996; Wachelke; Wolter, 2011; Sousa; Chaves, 2023). In this approach, SRs are composed of two interdependent systems: the central (or core) system and the peripheral system. Such systems contain a set of information, beliefs, and opinions about a given object.

The central system has a consensual nature, being formed by stable and consistent components and, therefore, becomes resistant to changes. It is the system that organizes and stabilizes the elements of a representation through social norms, and is therefore a generator of meaning for this representation. The peripheral system, on the other hand, is more flexible, negotiable, dynamic, and relates more intensely to behaviors, regulating and guiding them, in addition to legitimizing and contextualizing the components of the central system (Abric, 2001; Sá, 1996; Wachelke; Wolter, 2011; Sousa; Chaves, 2023).

Another phenomenon of social cognition that constitutes intergroup relations is the attribution of stereotypes. These stereotypes are like beliefs about specific aspects of a social category and are attributed to groups. They are part of the generalization process and, like SR, help individuals to symbolically organize the environment (Pérez-Nebra; Jesus, 2011; Techio, 2011).

Through the Theory of Intergroup Relations (Tajfel; Turner, 1979; Tajfel, 1982), it is possible to perceive stereotypes as components of the process of categorizing social groups, enabling individuals to identify and differentiate people who participate in different social groups, in addition to legitimizing behaviors between groups. Thus, stereotypes have the function of attributing positive representations to the endogroup (group to which the individual belongs) in relation to the exogroup (comparison group, to which the individual does not belong) in a context of conflict between groups.

3. METHODOLOGY

Through applied research, the Free Word Association Test (FWAT) was used as a data collection instrument, using the inducing terms “masculine clothing” and “feminine clothing”, with 256 respondents. The data were analyzed through Prototypic Analysis, performed using the Iramuteq software.

3.1 Participants

The sample consisted of 256 participants (respondents), being: 160 women, 93 men and 3 non-binary people (Mage = 32.12, SD = 8.82). The majority identified as heterosexual (N = 164; 64.1%), followed by bisexual (N = 39; 15.2%), gay (N = 35; 13.7%), lesbian (N = 12; 4.7%) and pansexual (N = 6; 2.3%). The majority of the sample was middle class (N = 121; 47.3%), identified as white (N = 141; 55.1%), and had completed higher education (N = 175; 68.4%). Regarding the political positioning of the participants, the majority identified as left-wing (N = 120; 46.9%), followed by center (N = 91; 35.5%), right-wing (N = 27; 10.5%), far left (N = 16; 6.3%), and far right (N = 2; 0.8%).

3.2 Instrument

Participants responded to the Free Word Association Test (FWAT), which aimed to identify the semantic field in relation to the attribution of gender to clothing. The terms “masculine clothing” and “feminine clothing” were used as inducers. Participants were asked to record the first five words that came to mind from the inducing stimuli.

3.3 Collection Procedures and Ethical Aspects

Participants were invited to collaborate in an online study in March 2023. The link to the survey was shared on the social media platforms WhatsApp and Instagram. Before the participants began, they were presented with the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF), which informed them about the guarantee of confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the research at any time, in addition to emphasizing the voluntary nature of participation. The FICF was created following the recommendations of Resolutions 466/12 and 510/16 of the National Health Council.

After consenting to participate, participants reported their demographic information (age, gender, sexual orientation, race, social class, education, and political position). Participants then responded to the Free Word Association Test (FWAT) based on two stimuli: “masculine clothing” and “feminine clothing”. Finally, participants were thanked for their participation.

It should be noted that the present study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Fortaleza under reference number 64127822.0.0000.5052.

3.4 Data Analysis

The data generated were analyzed using the Iramuteq software - R Interface for Multidimensional Textual Analysis and Questionnaires (Ratinaud, 2009). The words mentioned in the FWAT were lemmatized and subjected to Prototypic Analysis, which are techniques used to categorize social representation in a structural manner (Camargo; Justo, 2013; Wachelke; Wolter, 2011). This procedure was performed for each of the inducing stimuli.

This type of analysis calculates the frequency and order of the words evoked by the participants and generates a table composed of four quadrants (Figure 1): the Central Nucleus (CN) indicates the words that were evoked most frequently and most quickly; the Peripheral Zone is composed of the First Periphery (FP), which indicates words evoked with high frequency, but not immediately, and the Second Periphery (SP), which indicates words evoked with low frequency and not immediately; and the Contrast Zone (ZC), which indicates words that were evoked with low frequency, but quickly (Camargo; Justo, 2013; Wachelke; Wolter, 2011).

Figure 1. Prototypical Analysis

Source: Prepared by the authors (2024).

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Free Word Association Test (FWAT) was used to understand the participants’ social representations regarding the attribution of gender to clothing. Initially, the participants were asked to list the first five words that came to mind when they thought of the phrase “masculine clothing”. A total of 410 responses were obtained. Table 1 shows the main elements of the social representations about masculine clothing for the research participants.

Table 1. Prototypical Analysis of the FWAT for the stimulus “masculine

clothing”

Source: Prepared by the authors (2024).

In Table 1, it is possible to see that the main elements of the social representations about “masculine clothing” for the participants are strongly associated with the words “pants”, “shorts”, “shirt”, “suit” and “t-shirt”. These words, located in the first quadrant of Table 1, constitute the Central Nucleus (CN) of the social representation of the phenomenon in question for the sample, that is, they structurally present the notion most strongly shared by the group and the words with the highest frequency.

In the Peripheral Zones, located in the second and fourth quadrants of Table 1, other words emerged that illustrate the representation of masculine clothing for the participants. In the first periphery, illustrated in the second quadrant, words with high frequency and high evocation are located, so that they complement the meaning of the CN and protect it. For the respondents, the words listed with the highest frequency were “underwear”, “sneakers”, “cap” and “vest”.

In the second periphery, corresponding to the fourth quadrant of Table 1, are the words with the lowest frequency and highest order of evocation, more strongly related to the individual experiences of each participant. The words with the highest frequency were: “suit”, “social” and “comfortable”.

The Contrast Zone, located in the third quadrant of Table 1, corresponds to the elements that were readily evoked and with a below average frequency, indicating a possible change of direction in the social representation. Here, the words cited most frequently were: “blue”, “long pants” and “comfort”. It is noted that there is no significant contrast between the words in the other zones, which may indicate that the social representation of masculine clothing is stable.

The participants were then asked to list the first five words that came to mind when they thought of the expression “feminine clothing”. A total of 346 responses were obtained. Table 2 shows the main elements of the social representations of feminine clothing for the research participants.

Table 2. Prototypical Analysis of the FWAT for the stimulus “feminine clothing”

Source: Prepared by the authors (2024).

Table 2 presents the main elements of the social representation of “feminine clothing” for the participants. It was found that these elements are strongly associated with the words “dress”, “skirt” and “pants”, thus forming the Central Core of the representation.

In the Peripheral Zones, located in the second and fourth quadrants of Table 2, words emerged that illustrate the representation of feminine clothing for the respondents. In the first periphery, in the second quadrant, the words “bra”, “panties”, “shorts” and “cropped” are located, since they are the most evoked. In relation to the second periphery, corresponding to the fourth quadrant of Table 2, the words with the highest frequency were: “shorts”, “flowers” and “neckline”.

In the Contrast Zone, located in the third quadrant of Table 2, the most frequent words were: “skirts”, “colorful” and “shirt”. It is noted that there is no significant contrast between the words in the other zones, which may indicate that the social representation of feminine clothing is stable.

It is noted that there are differences in the evocations referring to the types of clothing related to each gender, with masculine clothing being represented by pieces that provide more comfort and mobility, in addition to being more serious than feminine clothing. In short, the attribution of gender stereotypes to the pieces of clothing by the research participants is noticeable. This result reinforces the idea of clothing as one of the most perceptible symbols of gender and social status, as stated by Crane (2006), since for the author, clothing is part of the process of creating social identities and constitutes a form of affirmation and production of behavior.

The differences in the way the research participants viewed “masculine” and “feminine” clothing seem to be part of an analysis process inherited from the 19th century, when clothing became part of the process of differentiation between the male and female genders (Kawamura, 2018; Crane, 2006) and occupied a privileged place, within a binary logic, in the process of demarcation and delimitation of gender boundaries (Zambrini, 2010; 2016).

The research results are in line with what was presented by Hyde (2005, 2019), based on the idea that, in terms of traits, skills, interests and behaviors, men and women do not fit into two completely distinct categories. This is because, individually, men and women can express a mix of attributes and behaviors considered “masculine” and “feminine”. Lennon et al. (2017) presented results that the use of specific items culturally informs biological sex; as an example, the author denotes the gender designation of babies’ bodies read as male or female through the use of the colors blue and pink.

Morgenroth and Ryan (2020) point to the hypothesis that the gender/sex binary is created and reinforced through gender/sex performativity, linked to the subject (man/woman), the costume (body and appearance), and the script (behaviors, mannerisms and preferences). This expectation can be perceived by the survey responses, in which there was recognition that clothing can reinforce gender stereotypes, as well as how much these create expectations about what each gender can or cannot wear. Thus, clothing can be understood here as an item of expression of identity, while also assuming the character of an instrument of social adaptation.

Akdemir (2018a) agrees that the way of dressing varies according to the social group occupied by the subject and that clothes carry visible signs of expression and identification through colors, models, fabrics and visual elements. Communication through clothing highlights norms that are shared by the members of a group and can become identifiable signs for those who are not part of that group. As suggested by Tajfel (1982) this phenomenon can be understood as part of the process of social categorization – in which the outgroup tends to be analyzed as a homogeneous group, that is, composed of members who are similar to each other. However, this analysis is based on generalization, which allows for a stereotypical view of the groups in question.

Dutra (2002) states that historically fashion is not seen as a masculine attribute, being attributed to frivolities and whims related to women. The survey responses bring this reality to light in the attribution of more fashion elements to “feminine clothing”, such as colors, prints and variety of items. At the same time, masculine clothing is attributed to being more serious and having a limited variety of colors and items.

Writing about the criticism that some feminists make of this binary logic that fashion distracts more women than men, Kawamura (2018) states that fashion can be understood as a mechanism for controlling female bodies that reduces women’s social, cultural, and intellectual horizons. They start to spend their time and money on beauty, and this becomes oppressive, generating a “false consciousness” of what they start to believe is a priority: clothes and appearance.

Akdemir (2018b) points out that fashion plays an important role in deconstructing gender stereotypes and that, currently, we can see how much the ways of dressing have been updated: presenting “feminized” masculine clothing and “masculinized” feminine clothing, in line with trends such as agender (Lee et al., 2020) and co-ed fashion (Githapradana, 2022). The results found in the research show that this discourse of a more diverse and subversive fashion to the norms of gender seems to be far from the reality of the participants whose processes of analysis and attribution of stereotypes is viewed through a binary lens.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Clothing is part of people’s daily lives and, in addition to having an objective function of protecting the body, it assumes social functions that go beyond the simple act of covering oneself. From being a social device to a symbol, the most notable of which is a symbol of social status and gender, clothing communicates something about those who wear it.

Over time, fashion has tended to reinforce gender stereotypes by dividing what is understood as masculine clothing and feminine clothing. This process is based on a binary logic of gender that permeates all instances of the social lives of people who begin to see the world through this lens.

The research participants tended to corroborate this binary logic in their reading of the process of gendering clothing. Using the FWAT, it was possible to get closer to the participants’ social representations of what could be “masculine clothing” and “feminine clothing” for them. “Masculine clothing” was assigned words that indicate practicality, seriousness and comfort, while “feminine clothing” was assigned words that indicate a greater variety of items and a focus on the aesthetics present in the assortment of colors and patterns.

It was noted that the words present in the Central Nucleus seem to be protected for both inducers, meaning stability in the social representations indicated by the participants. This data reinforces the idea of how much binary logic still operates in the way people understand and consume fashion products. Although there is the recognition of a subversive trend of gender in some movements within fashion – agender fashion, genderless fashion and co-ed fashion – this reality still seems to be far from the reality of most people.

This study made it possible to look at the development of future studies in the area of fashion, gender studies and SR that can consider specific realities of consumption, intersectionality with certain social markers, such as sexuality, race and generation, and the impacts of SR on the creation and production of fashion products. Some limitations were noted throughout this research, such as the method of accessing interlocutors via social networks, which limits access to people who are not present in this context.

Nevertheless, this research presents important contributions, one being scientific, in the production of knowledge in the areas of Fashion and Social Psychology, and the other social, by demonstrating to society how much clothing is one of the central elements within human relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Ceará Foundation for Support of Scientific and Technological Development (Funcap), the agency that financed this work.

REFERENCES

ABRIC, J C. Prácticas sociales y representaciones. México: Coyoacán, 2001.

AKDEMIR, Nihan. Visible Expression of Social Identity: the clothing and fashion. Gaziantep University Journal Of Social Sciences, [S.L.], v. 17, n. 4, p. 1371-1379, 2018a. http://dx.doi.org/10.21547/jss.411181. Disponível em: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jss/issue/39349/411181. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

AKDEMIR, Nihan. Deconstruction of Gender Stereotypes Through Fashion. European Journal Of Social Science Education And Research, S.L, v. 5, n. 2, p. 185-190, 2018b. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326662785_Deconstruction_of_Gender_Stereotypes_Through_Fashion. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

BRAGA, João. História da moda: uma narrativa. 6. ed. São Paulo: Editora Anhembi Morumbi, 2008.

CAMARGO, Brígido V.; JUSTO, Ana M.. IRAMUTEQ: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, [S.L.], v. 21, n. 2, p. 513-518, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/tp2013.2-16. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S1413-389X2013000200016&script=sci_abstract&tlng=en. Acesso em: 25 mar. 2024.

CALANCA, Daniela. História social da moda. São Paulo: Senac, 2011.

CRANE, Diana. A moda e seu papel social: classe, gênero e identidade das roupas. 2. ed. São Paulo: Senac, 2006.

DUTRA, J. L. “Onde você comprou esta roupa tem para homem?”: a construção de masculinidades nos mercados alternativos de moda. In: GOLDENBERG, Mirian (org.). Nú e vestido: dez antropólogos revelam a cultura do corpo carioca. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2002. p. 359-411.

FASHIONUNITED. Global fashion industry statistics – International apparel. 2016. Disponível em: https://fashionunited.com/news/global-fashion-industry-statistics/2016042011023. Acesso em: 15 de abril de 2023.

GITHAPRADANA, Dewa Made Weda. Aesthetics and Symbolic Meaning of Androgynous and CO-ED Style Trends in Men’s Fashion. Humaniora, [S.L.], v. 13, n. 1, p. 23-32, 15 fev. 2022. Universitas Bina Nusantara. http://dx.doi.org/10.21512/humaniora.v13i1.7378. Disponível em: https://journal.binus.ac.id/index.php/Humaniora/article/view/7378. Acesso em: 15 de abril de 2023.

GODART, Frédéric. Sociologia da Moda. São Paulo: Senac, 2010.

HYDE, Janet Shibley. The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, [S.L.], v. 60, n. 6, p. 581-592, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.6.581. Disponível em: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-606581.pdf. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

HYDE, Janet Shibley; BIGLER, Rebecca S.; JOEL, Daphna; TATE, Charlotte Chucky; VAN ANDERS, Sari M.. The future of sex and gender in psychology: five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, [S.L.], v. 74, n. 2, p. 171-193, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000307. Disponível em: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-32185-001. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

KAWAMURA, Y. Fashion-ology: an introduction to fashion studies. 2. ed. Londres: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

LEE, Hoe Ryung; KIM, Jongsun; HA, Jisoo. ‘Neo-Crosssexual’ fashion in contemporary men’s suits. Fashion And Textiles, [S.L.], v. 7, n. 1, p. 1-28, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40691-019-0192-2. Disponível em: https://fashionandtextiles.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40691-019-0192-2. Acesso em 16 de abril de 2023.

LENNON, Sharron J.; ADOMAITIS, Alyssa Dana; KOO, Jayoung; JOHNSON, Kim K. P. Dress and sex: a review of empirical research involving human participants and published in refereed journals. Fashion And Textiles, [S.L.], v. 4, n. 1, p. 1-21, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40691-017-0101-5. Disponível em: https://fashionandtextiles.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40691-017-0101-5. Acesso em: 23 mar. 2024.

LIPOVETSKY, Gilles. O império do efêmero: a moda e seu destino nas sociedades modernas. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2009.

MOSCOVICI, Serge. Representações sociais: investigações em psicologia social. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2017.

PÉREZ-NEBRA, Amalia Raquel; JESUS, Jaqueline Gomes de. Preconceito, Estereótipo e Discriminação. In: TORRES, Cláudio Vaz; NEIVA, Elaine Rabelo (org.). Psicologia social: principais temas e vertentes. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. Cap. 10. p. 219-237.

SÁ, Celso Pereira de. Núcleo central das representações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 1996.

MORGENROTH, Thekla; RYAN, Michelle K.. The Effects of Gender Trouble: an integrative theoretical framework of the perpetuation and disruption of the gender/sex binary. Perspectives On Psychological Science, [S.L.], v. 16, n. 6, p. 1113-1142, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745691620902442. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32375012/. Acesso em: 23 mar. 2024.

RATINAUD, P. Iramuteq: interface de r pour les analyses multidimensionnelles de textes et de questionnaires, 2009. Disponível em: www.iramuteq.org. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2024.

SOUSA, Yuri Sá Oliveira; CHAVES, Antonio Marcos. Representações Sociais. In: TORRES, Ana Raquel Rosas et al (org.). Psicologia Social: temas e teorias. 3. ed. São Paulo: Blucher, 2023. Cap. 8. p. 277-306.

TAJFEL, H. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Annual Review Of Psychology, [S.L.], v. 33, n. 1, p. 1-39, 1982. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245. Disponível em: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1982-12052-001. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2024.

TAJFEL, H; TURNER, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In: AUSTIN, W G; WORCHEL, S (ed.). The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, 1979. p. 33-47.

TECHIO, E. M.. Estereótipos Sociais como Preditores das Relações intergrupais. In: TECHIO, Elza Maria; LIMA, Marcus Eugênio Oliveira. (Org.). Cultura e Produção das Diferenças: estereótipos e Preconceito no Brasil, Espanha e Portugal. Brasília: Technopolitik, 2011, p. 21-75.

WACHELKE, João; WOLTER, Rafael. Critérios de construção e relato da análise prototípica para representações sociais. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, [S.L.], v. 27, n. 4, p. 521-526, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0102-37722011000400017. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/ptp/a/bdqVHwLbSD8gyWcZwrJHqGr/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2024.

ZAMBRINI, Laura. Modos de vestir e identidades de género: reflexiones sobre las marcas culturales sobre el cuerpo. Revista de Estudios de Género Nomadías, S. L., n. 11, 2010. Disponível em: https://nomadias.uchile.cl/index.php/NO/article/view/15158. Acesso em: 20 de março de 2023.

ZAMBRINI, Laura. Olhares sobre moda e design a partir de uma perspectiva de gênero. dObra[s] – revista da Associação Brasileira de Estudos de Pesquisas em Moda, [S. l.], v. 9, n. 19, p. 53–61, 2016. DOI: 10.26563/dobras.v9i19.452. Disponível em: https://dobras.emnuvens.com.br/dobras/article/view/452. Acesso em: 20 de março de 2023.